Fashion & Memory: Bianca Isabel Garcia

A fashion journey through diaspora and decolonisation

Lola Dely (Bianca’s great-grandmother) in the Pineda Bros. Furniture store. Image courtesy of Viyo Pineda.

For artist and researcher Bianca Isabel Garcia, fashion is a language through which one can read history and stitch together memories. Born in Baguio, Philippines, and now based in Toronto, she translates the traditions of her homeland into vibrant confrontations of resistance and repair, piecing together the fragmented identity of the diasporic experience. Through her creative practice, she invites viewers to see cloth as a layered text of loss and the possibility of generational healing.

Lola Dely (Bianca’s great-grandmother) and Lolo Viyo (her great-uncle) with visitors in front of the Pineda Bros. Furniture store. Image courtesy of Viyo Pineda.

Tita Anna and Tita Tina (Bianca’s aunts) in the Pineda Bros. Furniture truck. Early 1970s. Image courtesy of Viyo Pineda.

Garcia’s story begins with a family whose livelihood was bound to craft and survival. During World War II, her great-grandfather, Lolo Domitilo, ran a business selling bakya, wooden clogs. With the war’s end, he and his wife, Lola Dely, established Pineda Bros. Furniture, the first shop of its kind in Baguio. Together, the couple built a family business selling handmade wooden furniture and textiles, supporting their children through the labour of local craftsmanship.

That inheritance echoed through generations. Garcia’s aunt carried it on through a vintage store, and her parents through lessons in sewing and mending. What might appear as mere practical skills became, for Garcia, sacred rituals of care and deliberate acts of preservation. “I found comfort and connection to my family through this work,” she reflects. “It centres material objects that are treasured in a way outside of consumerist throwaway culture.” These gestures of making and repair form the foundation of her creative practice today.

Bianca’s dad wearing a striped barong at a wedding. Image courtesy of Ligaya Pineda Balatero.

Bianca’s mom at the Baguio General Hospital beauty pageant in 1994. Her outfit featured an Indigenous Cordilleran skirt. Image courtesy of Marsha Lou Garcia.

Yet Garcia’s grounding in Philippine culture was disrupted when her family relocated to Georgia in the United States. Suddenly, she was thrust into a new world where belonging often meant erasing difference. Like many children of migration, she was torn between the pressure of fitting into her “new homeland” and the haunting pull of what she left behind. Rather than rejecting this tension, Garcia made it her subject, tracing her roots through her family history and larger forces of colonialism.

A turning point came when she uncovered the hidden past of her birthplace. Baguio was once Kafagway, the ancestral land of the Ibaloi people, seized and transformed by American colonisers into a resort for elites. “When I learned about this history of my hometown, it felt like I was American before I ever landed in ‘America’,” she reflects. That discovery reframed what she had long carried as “deeply ingrained shame,” evolving it into an ongoing process of dismantling the colonial weight that had shadowed her even before birth.

Bianca modeling a terno in Athens, Georgia in 2019. Photo by Frankie Cole.

Bianca in Atomic vintage store in Athens, Georgia in 2019. Photo by Tatim Kilosky.

In Georgia, Garcia sought connection by turning toward her heritage. She immersed herself in Filipino cultural life, learning folk dances and organising cultural fashion shows. The first time she wore a Filipiniana dress, she describes, was an act of reclamation, an embodied declaration that her heritage could be worn proudly, on her terms. This fashion awakening deepened at Atomic, a vintage store in Athens where Garcia worked. There, vintage clothing became a tool of self-discovery. “Not only did I build fashion skills and knowledge, but Atomic also provided a space where I felt safe and encouraged to nurture my creative expression and critically reflect on how race, class, and gender colour my lived experience,” she recalls.

These lived experiences sharpened into academic inquiry when Garcia pursued a Master’s in Fashion Studies at Toronto Metropolitan University. After she received her degree, she began independent research aimed at a central question: how does empire inscribe itself on the body? She examined how American colonisers weaponised beauty and fashion in the Philippines, while obscuring violence and generating profit. Here, she drew on the work of scholars like Genevieve Clutario, whose Beauty Regimes: A History of Power and Modern Empire in the Philippines, 1898-1941 (2023) exposes how beauty pageants and fashion industries became tools of imperial control. For Garcia, such scholarship is not abstract theory, but a mirror reverberating through her own family’s story, connecting academic critique to lived experience.

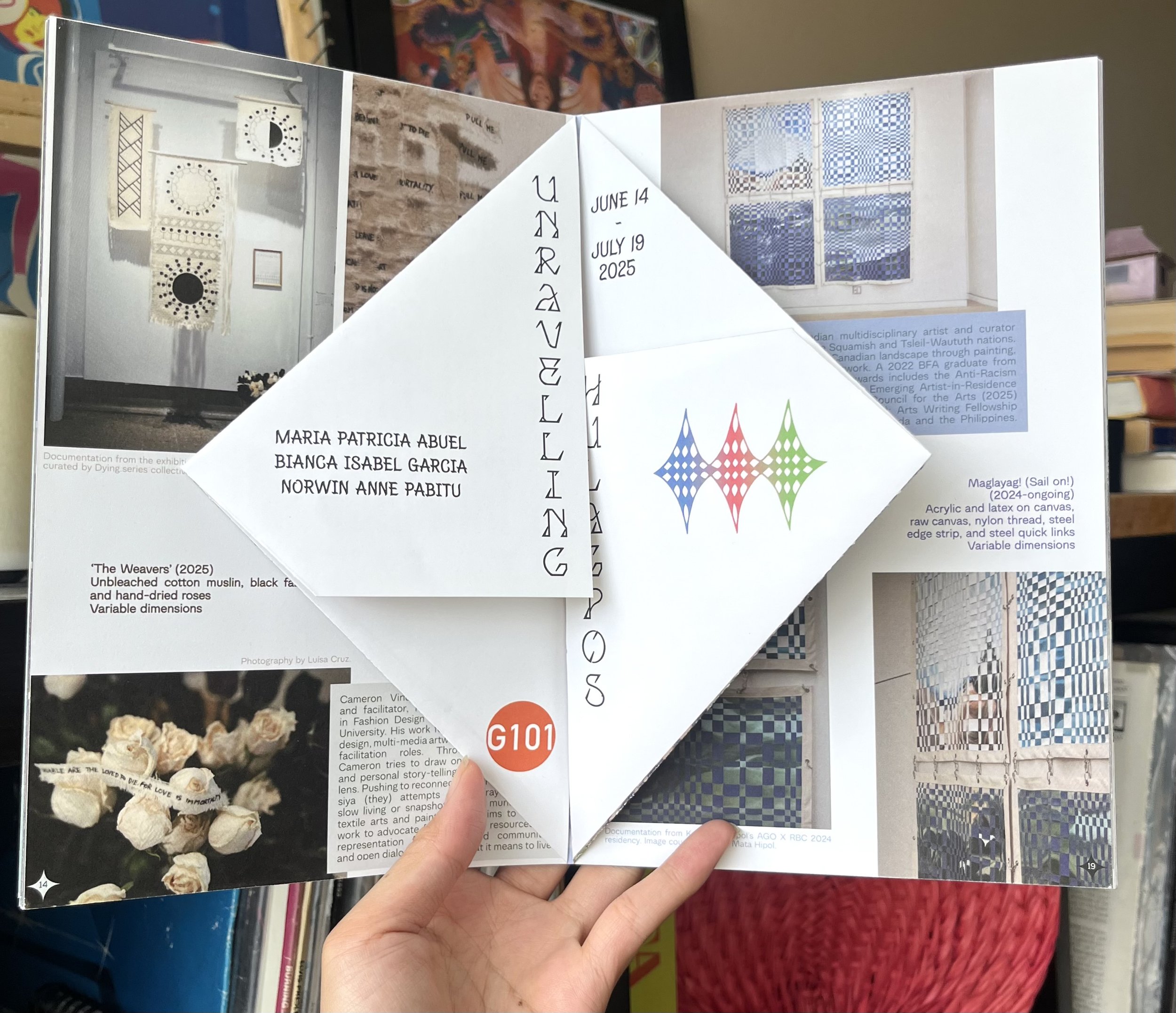

Unravelling (2025) exhibition at Gallery 101, Ottawa, Ontario. Image courtesy of Bianca Isabel Garcia.

Habilin zine centerfold. 2025. Image courtesy of Bianca Isabel Garcia.

Garcia refuses to separate theory from practice. Instead, she lets scholarship seep directly into making, dissolving the line between academic inquiry and artistic expression. In Toronto, she co-founded habi habi po, a non-profit collective with Filipino/a/x artists Norwin Anne Pabitu and Maria Patricia Abuel, dedicated to sustaining Philippine cultural heritage in the diaspora. Their recent multidisciplinary exhibition, Unravelling (2025), paired with an accompanying zine, drew bold connections between the fast-fashion waste crisis and longer histories of U.S. imperialism in the Philippines and Canadian settler colonialism. At the same time, it honoured the sustainable ingenuity of their Filipino foremothers, whose practices of mending and weaving offered both survival and resistance.

Parol-inspired textile sculpture, part of Nosebleed (2025). Image courtesy of Kristina Corre, Gallery 101.

The personal and political converge most powerfully in Garcia’s solo works. Nosebleed (2025) is a meditation on the systematic erasure of language as a colonial weapon. Using well-worn denim pieces from her mother and garments from her childhood, Garcia hand-stitched and screen-printed intimate messages, oscillating between grief and reconciliation. One line addresses her mother directly: “I’m sorry I blamed you, it’s not your fault.” Another turns inwards: “As I dig up my roots, I make way for new life.” These stitched confessions transform fabric into testimony, creating what Garcia calls “a release for my spirit and my inner child.”

Pabitin “candy” and “gifts” in Kamalayan Playground (2025) installation by Bianca. Ottawa, Ontario. Image courtesy of Kristina Corre, Gallery 101.

Bianca reaching for toys hanging from a pabitin during her second birthday party. Baguio, Philippines. 1999. Image courtesy of Marsha Garcia.

Hopscotch basahan woven by Bianca from Kamalayan Playground (2025), Ottawa, Ontario. Images courtesy of Kristina Corre, Gallery 101.

Similarly, Kamalayan Playground (2025) reshapes memory as critique. Garcia reimagines pabitin, a beloved Filipino children’s game where prizes dangle from a bamboo grid, drawing direct inspiration from her own childhood. However, in her version, the treats are replaced with colonial-era photographs, comics, and advertisements, representing the symbolic “rewards” of American influence. On the floor, a hopscotch mat, created with scrap fabric using the basahan weaving technique. spells out k-a-m-a-l-a-y-a-n, the Tagalog word for “political consciousness.” The installation asks viewers to approach history with the same restless curiosity of a child at play. “It’s a space of learning and transformation,” she explains, “an unapologetic curiosity and an ability to discern the truth.”

Hopscotch basahan woven by Bianca from Kamalayan Playground (2025), Ottawa, Ontario. Images courtesy of Kristina Corre, Gallery 101.

For Garcia, excavating the past is an act of emotional labour, charged with vulnerability and courage. Her work exists in tension, between the “rage” ignited by colonial narratives and the “deep relief” found in her family’s resilience against cycles of poverty. Making such pain visible can bring forth feelings of anxiety. “I have been terrified to be so vulnerable,” she admits, confronting displacement and unbelonging. Yet, she draws strength from a community of Filipino/a/x artists, finding joy and the reassurance that she is not alone. “They have held my fears of not being enough with so much compassion,” she reflects. Within this circle, Garcia has discovered a vital truth: engaging with one’s heritage can be deeply “meaningful and authentic,” while still leaving room for play and laughter, even when rooted in generational pain.

Looking ahead, Garcia continues to explore the diasporic body as a site of memory. Her next project is a multi-genre zine exploring her complex relationship with her mother tongue through the lens of Filipino food. In this work, the mouth and tongue become vessels for identity and remembrance, a space where language, food, and memory converge.

Garcia’s practice transcends the conventional bounds of fashion, reimagining it as a medium for healing, storytelling, and collective reckoning. By transforming personal grief into collective art, she offers a radical framework for reflection and restoration. Her work asks viewers not only to observe, but also to excavate their own roots, navigating the vulnerable spaces of self and community. In her hands, fashion becomes a map of memory, connecting past to present, guiding us toward a more conscious, compassionate future.

To learn more about Bianca Isabel Garcia, please visit her website or connect with her on Instagram.

About the Writer

Faith Cooper is the creator of the Asian Fashion Archive. She holds master’s degrees from the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York and from Fu Jen Catholic University in Taiwan, where she researched Taiwanese fashion and cultural identity as a Fulbright Student. Faith is now pursuing a PhD in history at the National University of Singapore, focusing on the cultural history of women’s sartorial developments in mid-twentieth-century Singapore.