Khmer, English & French: 100 Fashion and Textile Terms

Decolonising fashion studies in Cambodia

E-publication cover of 100 Fashion and Textile Terms, 2025. Image courtesy of Magali An Berthon.

100 Fashion and Textile Terms in Khmer, English and French is a trilingual glossary that begins to address gaps in language and culture in the study of Cambodian fashion and textiles. The open-access online resource invites contributions, revisions and conversations. It is created by Magali An Berthon, with illustrations by Sao Sreymao. In this article, we hear from them about the inspirations and motivation for the project.

Magali An Berthon presenting the project on December 3 at the American University of Paris. Image courtesy of Magali An Berthon.

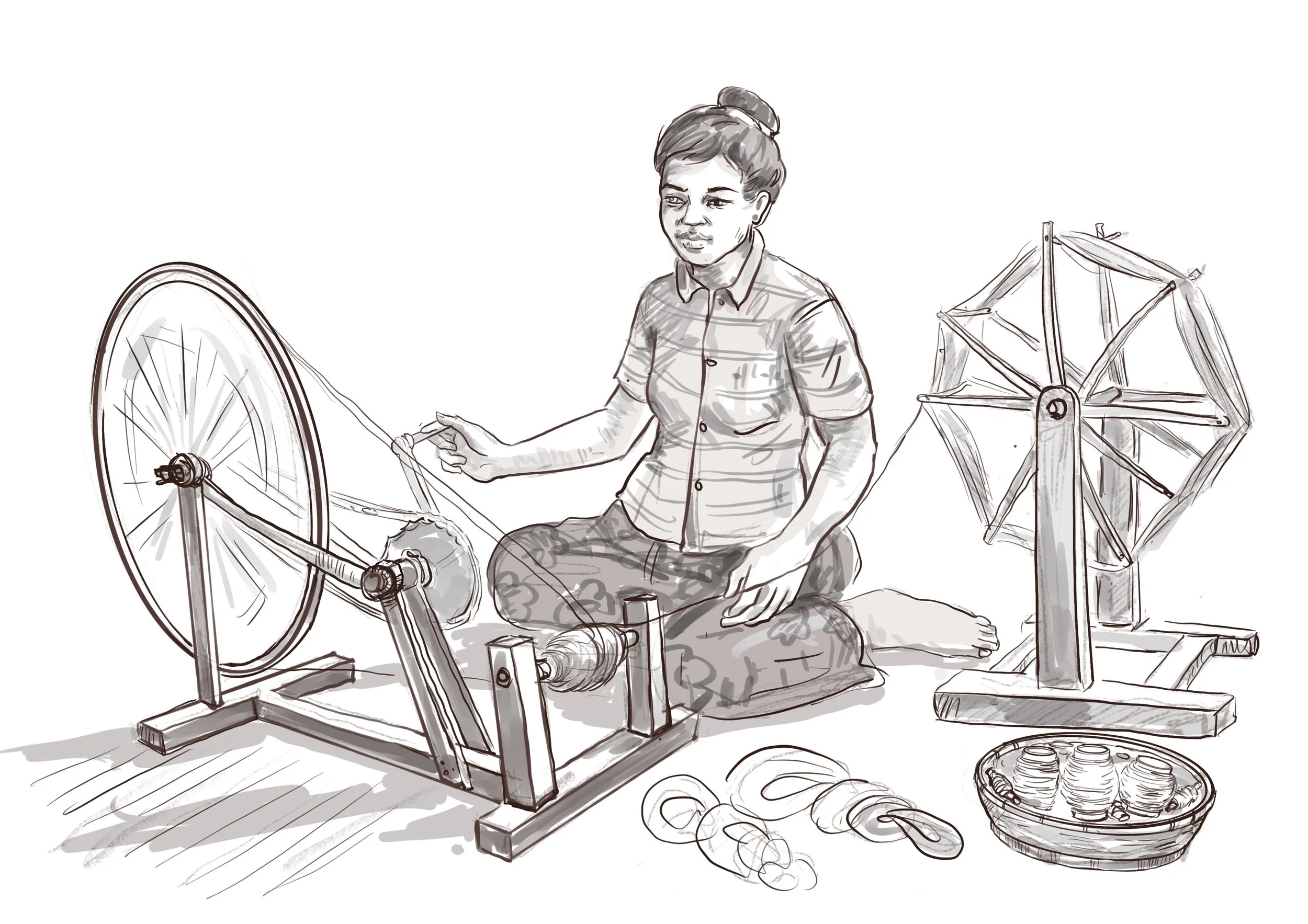

Illustration of artisan spinning silk by Sao Sreymao for 100 Fashion and Textile Terms (2025). Image courtesy of Magali An Berthon.

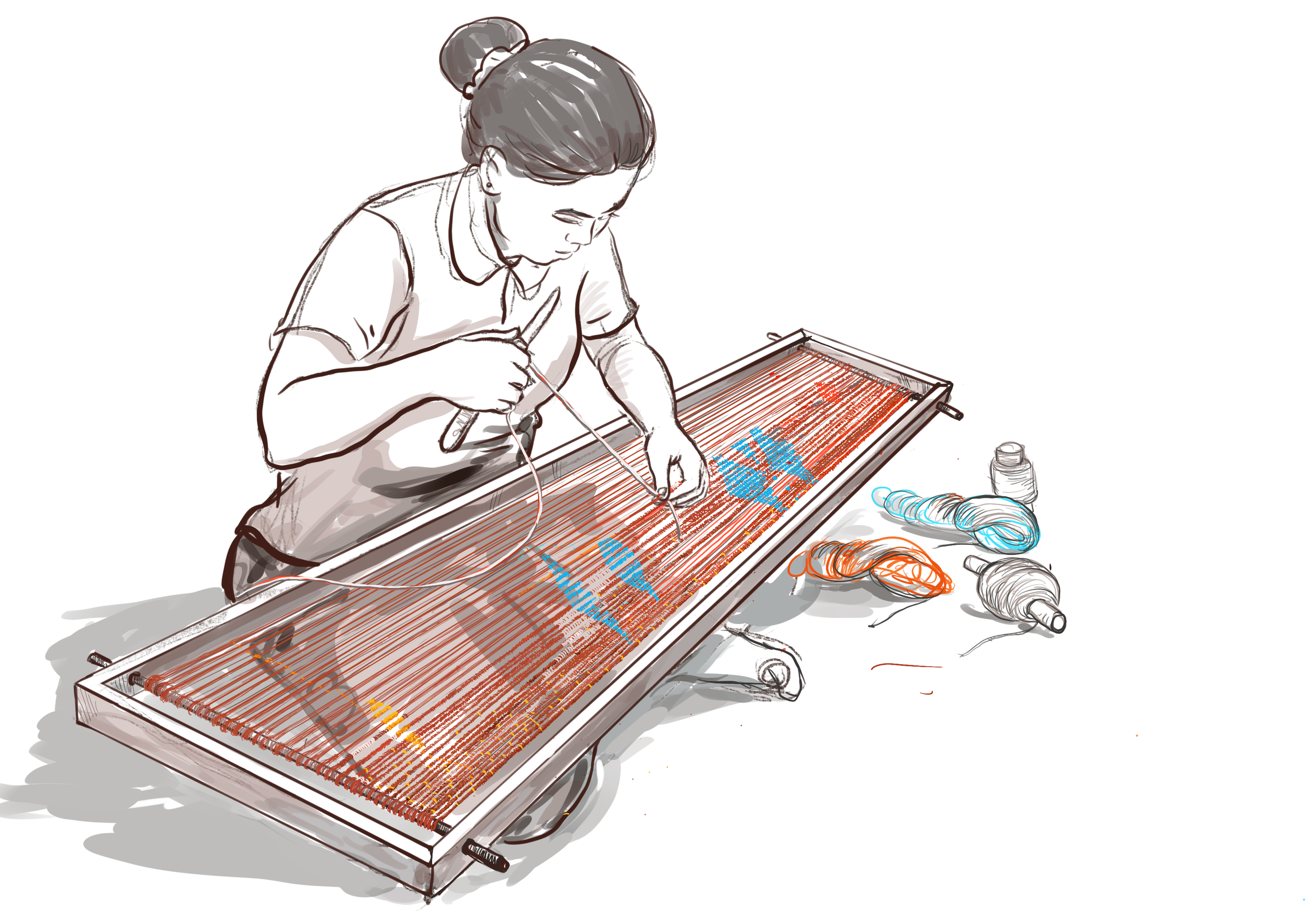

Illustration of an artisan tying threads on a traditional loom by Sao Sreymao for 100 Fashion and Textile Terms (2025). Image courtesy of Magali An Berthon.

Magali, what motivated the project, and why is it important, and timely to produce this publication?

One of the motivations behind this project comes from understanding that so much of the knowledge on weaving, fibers, dyes, textiles, and clothes was lost during and after the civil war and the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia in the 1970s. Weavers and fibre producers stopped their practice, especially the ancestral production of silk weaving and ikat textiles that were deeply linked to ceremonial and ritual aspects of people’s lives. Knowledge about techniques, looms, and equipment, as well as styles and motifs, was severely affected. It feels particularly relevant to develop a project around identifying and defining key terms in fashion and textiles, with the hope of building this glossary through time.

On a personal level, it has also been part of my research practice for about a decade to ask weavers about specific terms in Khmer, so I could record them. Interestingly, in Cambodia, some terms about motifs, tools, or practices can vary from one village to another. The language may fluctuate, which makes it challenging but also interesting. The idea has been to share this glossary as an innovative open-access resource that could benefit people, students, practitioners focusing on Cambodian textiles and dress, and working in English, French, and Khmer.

How has the project been funded?

I have been gathering terms and ideas of terms for several years now through different periods of fieldwork and research on Cambodian textiles and dress in the twentieth history. But the glossary in its current form was developed with the support of the John Lewis Fund offered by the American University of Paris, where I teach.

How was the work divided among the project team members?

The process was a collaborative effort, as I envisioned it in the first place. Khmer is not my mother language, so it was crucial to involve Khmer speakers and experts. I developed the glossary of 100 terms in dialogue with Moeung Seyha, a Phnom Penh-based researcher who worked as a translator on the project. From there, I also discussed with colleagues from the Centre for Textile Research at the University of Copenhagen who were quite versed in textile and fashion terminology in different contexts. My colleague Susanne Lervad helped me organise the glossary into relevant Categories: fibres, dyes, weaving, types of textiles, types of clothes and so on. I also collaborated with Morten Grymer-Hansen on the digital database of terms on Airtable, which is a user-friendly and visually engaging interface to share images and data. Once I had the terms, I established a list of terms that felt important to illustrate, which is what I shared with Sreymao. We discussed them, I shared pictures for reference, and then Sreymao worked on the sketches, some of them in black and white and others with colour.

How long did the project take from ideation to publication?

Not counting the identification and collection of terms that happened in the long run, the project took about six to eight months to develop. I worked on the long definitions in English and French, and coordinated the digital database development, the illustrations, and the electronic book design with my different collaborators. Finally, I worked on finding a printer and collaborated with the Communications department at my university to put together a webpage that would introduce the project and share the glossary database.

How did you make the selection of the terms to include in the 100 terms?

Though not exhaustive, the selection of terms is intended to be comprehensive. It is a challenge to reduce such a strong textile culture into a hundred words. The goal was to cover as many facets of textile and fashion production as possible, starting with materials and techniques. The glossary is organised into categories, including fibres and raw materials, dyes, textile techniques, sewing techniques, types of textiles, clothing, and preventative conservation.

I wanted to add conservation terms for potential museum professionals in Cambodia or working on Cambodian objects. Some of the etymology of Khmer fashion terminology originates from French, reflecting Cambodia’s colonial past. Other terms connect with a history of technological development with textile machinery, including sewing machines in the twentieth century. The glossary also contributes to the ongoing effort to decolonise fashion studies by redressing marginalised histories and decentralising knowledge production. In that regard, this project provides a didactic and user-friendly model for other terminology databases on fashion and textiles that include technical vocabulary, practices, objects, and materials.

The glossary also contributes to the ongoing effort to decolonise fashion studies by redressing marginalised histories and decentralising knowledge production.

What were the challenges you faced in putting this publication together?

The process of translation took time. There was a lot of back and forth to ensure the terms were appropriately identified and translated in Khmer. Since I do not speak Khmer well enough, I relied on Seyha to research certain terms further and verify their meanings. This complexity also speaks to the loss of knowledge and difficulty in accessing knowledge on textile materials, techniques, and dress in Cambodia. In the pre-Khmer Rouge era, textiles were central in Cambodian daily life. People had strong material literacy and learned about textiles and weaving in their families or villages. Now, this feels more remote, especially for young people in urban areas.

What are you most proud of for this publication? And aside from the publication itself, what are the other outputs for the project?

I am very happy about how it all came together with limited funding, a lot of goodwill, and energy from all participants. It was important to launch the project, so it exists, with the possibility to build on it and potentially bridge new collaborations with international academic partners.

Will there be a next installment, with say the next 100 terms?

The printed book is very much a 1.0 version of the glossary in its current state. There is more work to do on the existing 100 terms. The database will be expanded with additional images and long definitions in Khmer and French. In a second phase, other terms or themes could be developed, leading to an updated volume.

Illustrator Sao Sreymao at the American University of Paris. Image courtesy of Magali An Berthon.

Sreymao, how did you come to work on this project?

I joined the project through an invitation from Magali, to contribute my illustrations.

What made you say yes to this project?

I have a long-standing interest in Cambodian textiles and in exploring them through different forms of artistic practice. When Magali approached me, I saw the project as an opportunity to learn and to engage with different perspectives on Cambodian textiles. This desire for learning was a key motivation in my decision to participate. Additionally, collaboration and contributing to educational resources are central to my practice. I appreciate the project’s intention to bridge academic language and a broader audience, and I saw it as a meaningful opportunity to contribute visually to a collective process of knowledge-building.

How many illustrations did you create, and why these particular ones and not others?

In total, I created 23 illustrations. Each image was developed to clarify specific details that are often easily misunderstood or overlooked in photographs. Some of the illustrations were also selected because they refer to older documents, practices, or tools that have disappeared or are now represented in similar ways. In these cases, illustrations allow me to explain and contextualise elements that would be difficult to convey through existing visual material alone.

What are you most proud of for your contribution to this publication?

I am proud to be part of a documentary project that supports the preservation of textile knowledge. This publication is not only for Khmer readers, but for an international audience interested in learning about the words, techniques, and meanings embedded in traditional textiles. I value the opportunity to help raise awareness of why these cultural practices must be protected.

Access to the project 100 Fashion and Textile Terms in Khmer, English and French is available here, and here.