The Sartorial Eclecticism of Queen Sirikit

Fashion, politics, and Thai national identity

Sirikit Kitiyakara is a monarch whose sartorial eclecticism has left an indelible mark on the nation’s cultural memory. Throughout the seventy-year reign of her husband, Bhumibol Adulyadej, she developed a specific and individual style that set her apart as one of the most fashionable among modern royals today. Inducted in 1965, she reigns besides icons such as Grace Kelly and Farah Pahlavi in the International Best-Dressed List Hall of Fame—the brainchild of powerhouse publicist Eleanor Lambert whose oeuvre includes the founding of New York Fashion Week, the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), and the Met Gala.¹ A closer examination of her fashion choices, however, reveals that this image is not merely a reflection of personal taste and aesthetic sensibility, but the result of a more complex and intentional process inextricably bound up with national and international politics.

Sirikit’s image as style icon was born in 1960, at the height of the Cold War, when she accompanied the king on a historic tour to fifteen Western nations from the Free World faction. The carefully crafted itinerary included stops in New York, London, Paris, Rome, and other high-profile cities, and both serious and light-hearted activities that ranged from official state banquets to a day spent at Disneyland with their children. In addition to building and rebuilding diplomatic relations, this was a highly publicised event designed to launch the royal couple onto the global stage as appealing symbols of Thai modernisation.² The agenda was individual and multifaceted, to be sure, but the collective aim was to promote an image of Thailand as successfully modernised in a Western mould and would therefore be a desirable ally in the Cold War battle. For the queen, fashion was the key media through which she carried out this political work. The cultivation of a sophisticated sartorial eclecticism in her ensembles, with attention to the symbolic significance of the clothing and accessories, as well as the designers involved in the making of her wardrobe, was significant to this project.

Queen Sirikit in Balmain, with King Bhumibol, received by Mayor John F. Collins and Mary Collins at Logan Airport, 7 July 1960. City of Boston Archives, public domain.

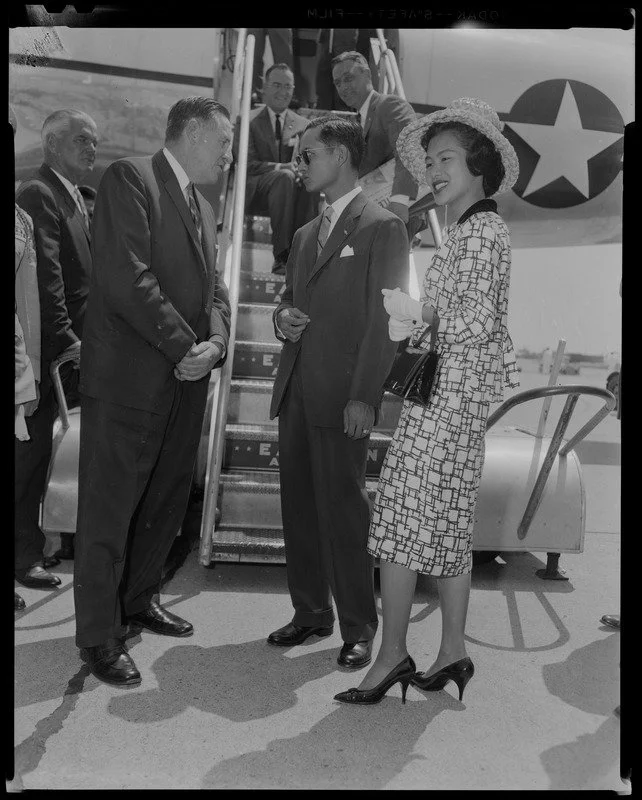

The king and queen of Thailand with Governor Foster Furcolo at Logan Airport, 7 July 1960. Boston Public Library, public domain.

In the 1960s, it was customary for Western royal and political figures to wear custom-made, high-fashion clothes designed in their own country or in Paris. Keeping with this norm, Sirikit enlisted Parisian couturier Pierre Balmain to design and execute the entirety of her tour wardrobe and to advise on the intricacies of wearing and styling the ensembles.³ Dress opens the site where practices of inclusion and exclusion operate, and the diffusion of the Western regime of sartorial propriety through networks of imperialism had long established the standardisation of dress practices on a global scale. Bangkok’s royals were well-versed in the intricacies of this politics, and beginning in the 1860s, strategically adopted Victorian dress etiquette to present themselves as modern and civilised in the eyes of Western powers.⁴ Although the age of Empire had passed, the West’s continued hegemony meant that presenting oneself as “modern” required the continued adherence to its standards of decorum. The choice of Balmain, therefore, allowed Sirikit to craft an image of Thailand that projected cultural refinement and European tastes.

Unlike her predecessors, Sirikit did not simply dress the part, but actively engaged in a culture of fashion. Her Balmain ensembles were in the modish styles of the time, many of which were picked from the Maison’s newly unveiled spring 1960 collection. Moreover, accessories of furs, wraps, coats, hats, and even raincoats and umbrellas were ordered to coordinate with the garments, and no combination was worn more than once in a country or region as repeating an ensemble was deemed discourteous. Fashion shows and shopping trips were also included in her schedule of activities.⁵ These efforts proved highly effective, and the international press responded with enthusiastic coverage with most of the attention focused on what the New York Times called “a huge and wonderful wardrobe of fairytale dimensions and a collection of jewels few could rival”.⁶ The diplomatic tour served a multifaceted agenda, one of its objectives being to enhance the crown’s visibility and, by extension, the institution’s relevance within domestic politics. Fashion, in this instance, became a tool of expansion that allowed Sirikit to craft a space for herself in the public sphere.

Queen Sirikit wears Thai national costume to a reception in Boston with the mayor and governor. City of Boston Archives, public domain.

But perhaps one of the most successful and lasting outcomes of the tour was Sirikit’s Thai creations, which would evolve into the official form of national dress. These are neo-traditional inventions that draw inspiration from royal textile heirlooms and photographic archives of nineteenth-century Siamese princesses and consorts to reimagine Thainess through Balmain’s materials and techniques.⁷ On the tour, the garments were worn interchangeably with Western gowns at formal state occasions, creating a striking visual and political statement that spoke to the nation’s uninterrupted sovereignty. In a regional context where national identities continue to be shaped by the legacies of colonialism, Thailand’s status as the only Southeast Asian nation to have avoided Western colonialism remains central to the state’s self-presentation. More significantly, however, is the way that Sirikit’s harnessing of press attention enabled her to debut, and thereby legitimise a national style on a global scale that not only honoured the legacy of her husband’s House of Chakri but enfolded her at its heart. Today, her creations are embraced as the standard of sartorial decorum for major ceremonial and formal events. For instance, Thailand’s national costume for the 2016 Miss Universe pageant and, more recently, Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra’s outfit for the ASEAN Summit gala dinner in October 2024 are both inspired by Sirikit’s designs.

Hirankrit Paipibulkul, designer for Thailand’s 2016 Miss Universe national costume, said he was inspired by watching old footage of Sirikit.⁸ Illustration from the official Instagram of Hirankrit Paipibulkul (@zomo.zomo).

Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra at the 44th and 45th ASEAN Summit gala dinner in Vientiane, Laos, 10 October 2024, from the official Instagram of Paetongtarn Shinawatra (@ingshin21).

Although it is usually relegated to the frivolous and, at best, entertaining realm of political paraphernalia, the case of Sirikit’s sartorial practice shows how fashion can carve a space for female political actors to not only participate but even lead in the public sphere. Unlike her husband, who wore uniform masculine dress to disavow his body as a site for interpretation, her cultivation of a sophisticated sartorial eclecticism was an invitation for discussion and thus, publicity. This attention to her appearance by the international press, in turn, enabled Sirikit to promote an idealised version of Thainess and Thai subjecthood that is inextricably bound to her dressed body. She did not only dress well, but she understood the politics of fashion and proved more than equal to the task of fashioning a nation that could serve both individual and national interests.

Notes

Melissa Leventon, Fit for a Queen: Her Majesty Queen Sirikit’s Creations by Balmain (Bangkok: Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles, 2016), 9.

Heidi Brevik-Zender, “Crypto-colonialism, French Couture, and Thailand’s Queens: Fashioning the Body Politic, 1860–1960,” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 42, no. 1 (2020): 101.

Leventon, Fit for a Queen, 11–13.

Maurizio Peleggi, “Refashioning Civilization: Dress and Bodily Practice in Nation Building,” in The Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas, eds. Mina Roces and Louise Edwards (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2008), 65–66.

Leventon, Fit for a Queen, 19, 30–31.

Gill Goldsmith, “130 Costumes by Balmain Set for Visit,” The New York Times, June 27, 1960, 28, https://www.nytimes.com/1960/06/27/archives/130-costumes-by-balmain-set-for-visit.html.

Kanjana Hubik Thepboriruk, “Dressing Thai: Fashion, Nation, and the Construction of Thainess, 19th Century–Present,” Journal of Applied History 2 (2010): 120.

“After Tuk Tuk Dress, Miss Universe Thailand Goes Back to Basic on National Costume,” Coconuts Bangkok, November 18, 2016, https://coconuts.co/bangkok/lifestyle/after-tuk-tuk-dress-miss-universe-thailand-goes-back-basic-national-costume/.

Sources

“After Tuk Tuk dress, Miss Universe Thailand goes back to basics on national costume”. Coconuts Bangkok, 18 November 2016, https://coconuts.co/bangkok/lifestyle/after-tuk-tuk-dress-miss-universe-thailand-goes-back-basic-national-costume/.

Brevik-Zender, Heidi. “Crypto-colonialism, French Couture, and Thailand’s Queens: Fashioning the Body Politic, 1860-1960”. Nineteenth-Century Contexts 42:1 (2020), 87-112

Leventon, Melissa. Fit for a Queen: Her Majesty Queen Sirikit’s Creations by Balmain. Bangkok: Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles, 2016.

Leventon, Melissa and Dale Carolyn Gluckman. “Modernity Through the Lens: The Westernization of Thai Women’s Court Dress”. Costume 47:2 (2013), 216-233.

Peleggi, Maurizio. “Refashioning Civilization: Dress and Bodily Practice in Thai Nation Building”. In The Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas, edited by M. Roces and L. Edwards, 65-80. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2008.

Thepboriruk, Kanjana Hubik. “Dressing Thai: Fashion, Nation, and the Construction of Thainess, 19th Century-Present”. Journal of Applied History 2 (2010), 112-128

Tregaskes, Chandler. “Celebrating the Style of Queen Sirikit of Thailand”. Tatler, 5 May 2020, https://www.tatler.com/article/queen-sirikit-of-thailand-style.

About the writer

Weerada Muangsook is an art and fashion historian whose research lies at the intersection between dress, identity, representation, and power. She is currently a PhD candidate in Art History at the University of St Andrews.