Fashion & Memory: Auguste Soesastro

Threads of Legacy in Transcultural Fashion

The KRATON black heavyweight crepe Beskap jacket. Image courtesy of KRATON.

The KRATON black heavyweight crepe Beskap jacket. Image courtesy of KRATON.

Since founding his label KRATON in 2008, Auguste Soesastro has redefined luxury by merging transcontinental elegance with sustainability and cultural preservation. From dressing high-profile celebrities like Dian Sastrowardoyo to presenting his work to former US First Lady Michelle Obama, he has cemented his place as a visionary, one whose designs are as much about storytelling as they are about style. Soesastro upholds Fair Trade standards, works with biodegradable natural textiles, and collaborates with master artisans across Indonesia. At the heart of his practice is a designer shaped not only by professional achievements, but also marked by a life lived across four continents and a lineage steeped in artistic legacy.

A portrait of Auguste Soesastro’s great-grandmother Mrs Gan Kay Bian wearing a kebaya in the Netherlands during the 1970s. Image courtesy of Auguste Soesastro.

Auguste Soesastro with his great uncle. Image courtesy of Auguste Soesastro.

Born in Jakarta, Soesastro’s journey began with a childhood shaped by navigating a global landscape of cultures. While living in the Netherlands, where his great-grandparents had emigrated in the 1950s and 1960s, he was deeply influenced by his grandmother. “I was always attracted to fashion in some way,” he recalls. “I remember my dad’s mother always dressed immaculately. She used to make her own clothes as well. The practice of sewing and making clothes was always present in my life. It was kind of natural.” That early exposure to fashion fostered a deep appreciation for craftsmanship, rooted in memory, place, and identity.

Auguste Soesastro’s father, Hadi Soesastro, wearing a surjan, alongside his cousin wearing a kebaya. Image courtesy of Auguste Soesastro.

Soesastro’s family later relocated to New York City, where he attended elementary school, while his father Hadi Soesastro, one of Indonesia’s most distinguished economists, taught at Columbia University. Though far from home, reminders of Indonesia remained close. “My father always wore batik,” Soesastro fondly remembers. “It was not popular to wear a batik shirt in the 1980s, especially a short-sleeved batik shirt worn to the classes he taught. It was very unusual.” This sartorial choice also became a significant form of cultural transmission. “He would explain to me, ‘This is batik. This is Indonesian. This is where we come from,’” Soesastro adds. “He wanted to make sure we understood that. He was very proud of being Javanese.” For Soesastro, batik was more than just a cultural symbol, but part of his lineage. His ancestry includes a long line of batik artisans, including his great-great-grandmother Tan Pang Soen, great-grandmother Gan Kay Bian, and great-aunt Tan Sin Ing. This legacy of craftsmanship, passed down across generations, would eventually become central to his identity as a designer.

Auguste Soesastro performing a Balinese dance during United Nations Day celebrations, as featured in The Canberra Times (29 October 1999). Image courtesy of Auguste Soesastro.

As a child, Soesastro became active in the local Indonesian student community, studying gamelan and Balinese dance, early expressions of a growing cultural consciousness. He later moved to Australia for high school, eventually pursuing a degree in architecture at the University of Sydney, followed by film and digital arts at the Australian National University. It was during his final year there, when he took a position at the National Gallery of Australia as a junior curator, specialising in Southeast Asian textiles and ethnographic arts. The role proved transformative, not only refining his curatorial skills, but deepening his connection to his own family history through material culture.

Auguste Soesastro encountering his great-grandmother Gan Kay Bian’s work for the first time, Canberra, 2004. Image courtesy of Auguste Soesastro.

Auguste Soesastro encountering his great-grandmother Gan Kay Bian’s work for the first time, Canberra, 2004. Image courtesy of Auguste Soesastro.

While working at the museum, Soesastro met with a batik collector. While examining her textiles, he identified a piece bearing the signature of his great-grandmother Gan Kay Bian, an accomplished batik entrepreneur. “This was the first time I saw anything that she made. I held it in my hands. It was surreal,” he recalls. Since the museum did not intend to acquire the piece, he contacted his father, and together they purchased it for their family, as they did not own any of her works. Today, batiks attributed to his family are held in prestigious collections worldwide, including the Los Angeles County Museum, the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, and the private archive of Singaporean curator and scholar Peter Lee. Lee, who owns around twenty-five pieces made by Soesastro’s family members, features several in his publication Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan Fashion in an Interconnected World, 1500-1950 (2018), including work by Soesastro’s great-aunt Tan Sin Ing of Sidoarjo, another pioneering batik entrepreneur. This encounter was only the beginning of Soesastro’s growing engagement with his familial legacy, but also the start of a professional devotion to promoting Indonesia’s material culture and craftsmanship.

At the age of twenty-four, Soesastro moved to Paris to study fashion at the prestigious L’Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne. Upon completing his studies, he returned to New York City, where he worked under Ralph Rucci, the first American designer in over sixty years invited by the French Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture to show in Paris. “I think he is one of the most incredible designers alive. He invented so many techniques,” Soesastro remarks. “My time at Ralph Rucci contributed to learning a way of pattern making that is much more practical than what I learned in France. Practical, but still couture. Ralph is in a league of his own.” It was this blend of rigorous training in Paris and hands-on industry experience in New York that shaped the foundation of Soesastro’s design ethos and his entry into the global fashion discourse.

The KRATON 'Beskap Langenharjan' cashmere jacket, cotton batik 'Dodot' overskirt, and rewoven batik ‘Cinde’ slacks, from Soesastro’s debut Spring 2010 NYFW collection. Left: Original design sketch. Right: Realised runway look. Images courtesy of KRATON.

In 2008, Soesastro founded KRATON, a label rooted in refined technique and transcultural elegance. Meaning “palace” in Indonesian, KRATON is more than a fashion brand. It is Soesastro’s vehicle for preserving and reimagining Indonesia’s rich sartorial heritage for the global stage. “I like the fact that I am starting to achieve what I set out to do, which is make modern versions of traditional dress for everyday wear,” he explained. “People are wearing it every day. I see people, whom I don’t know, on the streets, and they are wearing my creation, which is really nice seeing.” KRATON made its runway debut during New York Fashion Week in February 2009 at the Asia Society. Soesastro presented a collection inspired by Javanese silhouettes, incorporating silk and cashmere shawls produced by Indonesian cloth maker Bin House by Obin Komara. Following the death of his father in 2010, Soesastro returned to Jakarta, relocating his business there to be closer to his family.

Auguste Soesastro’s grandmother with her three sisters, Malang, East Java, 1960s. Image courtesy of Auguste Soesastro.

The KRATON imperial collar linen shirt paired with hand-drawn, naturally dyed batik wide-leg cotton trousers and matching shawl. Image courtesy of KRATON.

Since its beginning, KRATON has embodied a commitment to ethical production and craftsmanship. The brand has sourced handwoven textiles from artisan communities across Indonesia, including the Baduy villagers of Banten, weavers in West Bali, and songket cloth makers in West Sumatra. In a recent collection shown last September, Soesastro introduced hand-drawn batik on linen, marking a new experiment, closely aligned with his ancestral lineage. “I think it is very important for me to incorporate this craft that was practised by my great-grandparents and show it to the world as part of our heritage,” he says. “I am trying to honour them by working with artisans of top quality batik, so that I can preserve batik of a certain level.” Soesastro’s efforts to safeguard this legacy extends beyond design. He actively researches his family’s artistic contributions, using social media to identify additional pieces and consults contemporary scholarship in which their work is cited.

Studio portrait of Hamengkubuwono VII, Sultan of Yogyakarta, photographed by Kassian Cephas between 1870 and 1890. Collection of the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam.

The KRATON patchwork beskap jacket (2019), crafted from Italian suit wool. Image courtesy of KRATON.

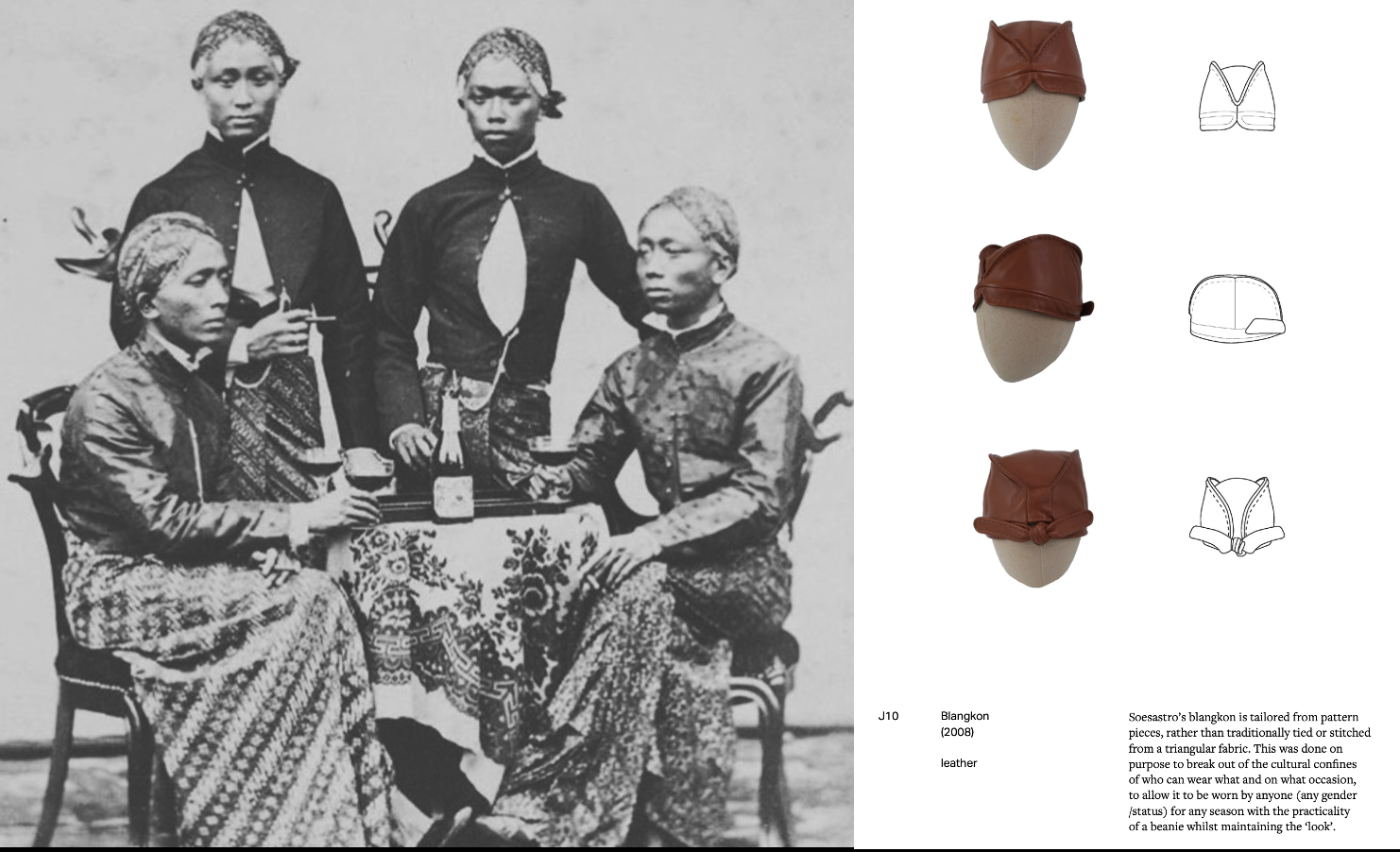

Among Soesastro’s early signature pieces is a patented reworking of the blangkon, a Javanese men’s headdress, which he reconfigured into an accessory for women. “I like this garçon idea in French fashion, men’s clothes for women, like cross-dressing,” he explains. “A lot of my womenswear is based on traditional menswear.” His designs often draw directly from historical references, as in the case of his patchwork beskap, a Javanese men’s jacket, crafted from leftover wool remnants. The concept emerged after encountering a late nineteenth-century portrait of Hamengkubuwono VII, the seventh sultan of Yogyakarta, which he saw at a museum in Amsterdam. Similarly, he deconstructed one of his father’s surjans, a classic pinstriped long-sleeved Javanese shirt, to study its construction. “The traditional fabric is scratchy, so I made this from a pin-striped Italian cotton fabric,” he said. “So it has the look, but it needs to be comfortable for everyday wear.” Through these acts of interpretation, Soesastro reinvents dress as a living memory that transcends generations, genders, and borders.

The KRATON surjan (2019), crafted from Italian cotton. Image courtesy of KRATON.

To date, Soesastro’s work has received international recognition, with presentations in fashion capitals such as New York City, Milan, and Jakarta. In 2023, his first large-scale exhibition, ꦢꦪꦤꦶꦁꦧꦸꦢꦶ – A Force of Subtleness, opened at The Warehouse, Plaza Indonesia. More than a retrospective, the exhibition traced his personal and creative evolution, shaped by themes of family legacy, identity struggles, and migration. “Every culture that I have encountered has given me some knowledge or information of how people do things differently,” he shares. “And that helped when starting my label. I wanted to bring Indonesian fashion to the world and to make it relevant.” When reflecting on the challenges of promoting and preserving Indonesian cultural heritage, he emphasises opportunity over difficulty. He says, “I think it is more exciting than challenging. The challenge is to choose what to present first and how to present it in a way that is attractive and relevant for an audience outside of Indonesia and younger generations in Indonesia.”

The KRATON blangkon (2008), made of leather. Image courtesy of KRATON.

In recent years, Soesastro has observed a growing curiosity among younger Indonesians in connecting with their cultural roots; a shift that accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. “We had an influx of people in their twenties who were interested in what we are doing and their culture,” he notes. “I am happy I can contribute to a little of it, because people are looking for traditional dress, but they do not want the old-fashioned traditional dress. That is where we come in.”

Rooted in his family’s legacy yet responsive to contemporary sensibilities, Soesastro remains committed to preserving and reimagining Indonesia’s sartorial traditions for a new generation. Looking ahead, he aspires to develop another exhibition, one that invites thoughtful discussions around cultural heritage. “The idea of identity is more important than ever, in such a borderless world,” he reflects, underscoring the urgency of amplifying non-Western perspectives within global cultural discourse. Through his work, Soesastro goes beyond preservation, fostering an intergenerational and transnational dialogue that bridges past and future, situating Indonesia within the global fashion discourse.

To learn more about Auguste Soesastro and KRATON, please visit the brand's website and follow him on Instagram at @kratonworld and @augustesoesastro.

About the Writer

Faith Cooper is the creator of the Asian Fashion Archive. She graduated from FIT, studying art and fashion history. Under the Fulbright programme, she is researching Taiwanese fashion and cultural identity at Fu Jen Catholic University in Taiwan. To learn more or connect with Faith, please visit her website.