Fashion & Books: Chandreyee Ray

Vogue Dialogues, Non-Fiction Writing and Reading

Fashion & Books is a monthly column where we speak to Southeast Asian creatives about the fashion and books they read, love and collect. This series dives into the ties between the worlds of fashion, the literary arts and independent publishing in and around the region.

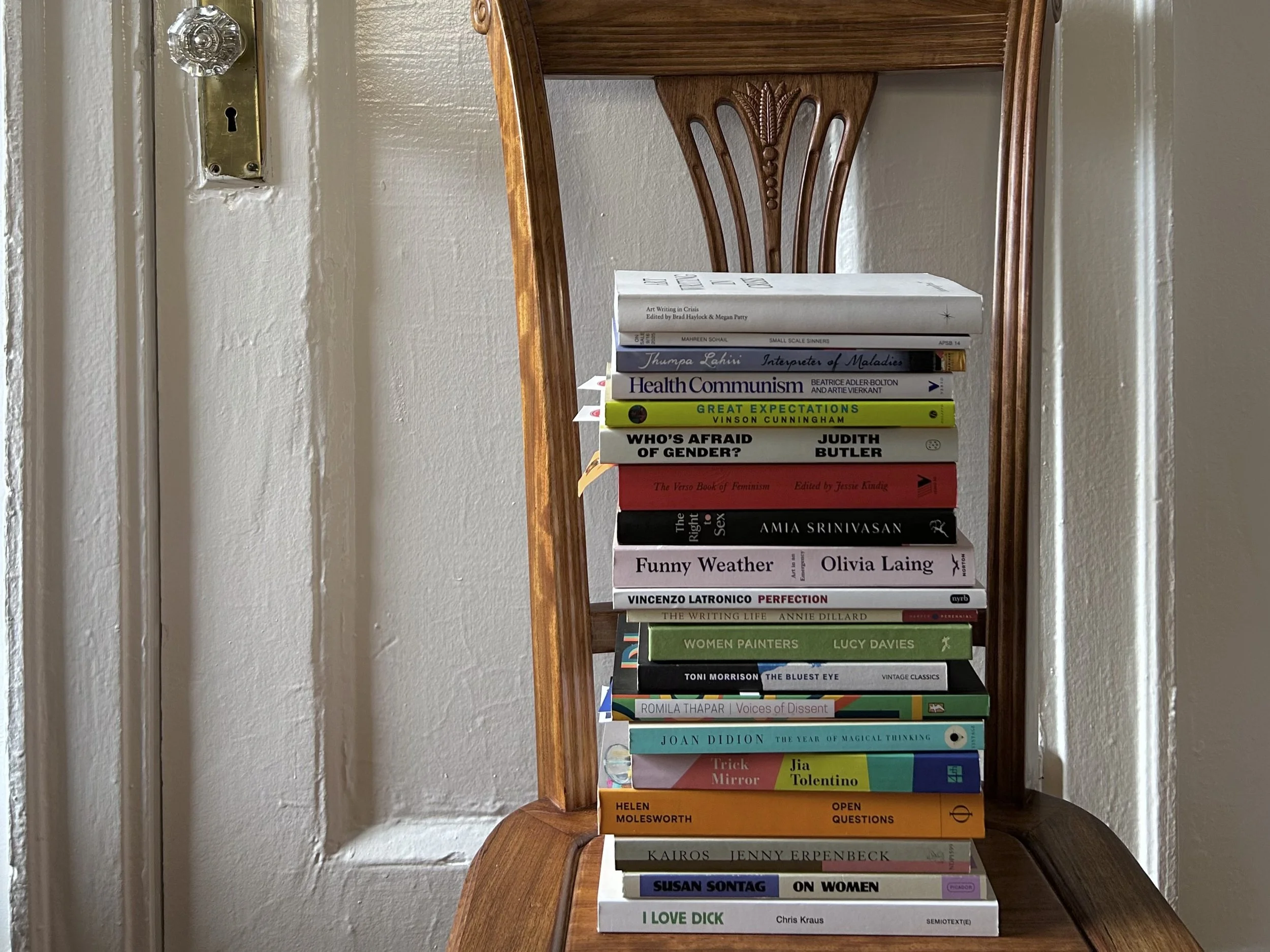

Ray’s stack of books she brought with her from Singapore to New York. Image courtesy of Chandreyee Ray.

Opening the column is Chandreyee Ray, who was until recently the associate lifestyle editor at Vogue Singapore. Over the course of a nearly three-hour Zoom call from her dining table, Ray, who is now based in New York while pursuing a MFA in Writing at Columbia University, shares what the intersection of fashion and books means to her.

Vogue Dialogues was Chandreyee’s brainchild in her time at the magazine. The series started with poet Pooja Nansi, founder of non-profit poetry press AFTERIMAGE, and former director of Singapore’s Writers Festival. This was followed by Amanda Lee Koe of Sister Snake and Ministry of Moral Panic fame, who described literary content in fashion magazines as reading about a “filled-in world”, then debut author Jemimah Wei of The Original Daughter; and to wrap it up, Usha Chandradas, lawyer, educator and co-founder of Southeast Asian art magazine Plural Art Mag.

The inception of the series was born from Chandreyee’s desire to expand fashion’s cultural reach through literature. Under her incisive vision, Vogue Singapore’s literary coverage evolved from book features in editor’s picks to a thoughtful body of work that engages key literary voices. “Just talking about Dialogues gives me the warm fuzzies because it’s the two things I love. It felt like a very natural collaboration, a crossover,” Chandreyee says with a smile.

Set against the backdrop of culturally significant spaces in Singapore: Basheer Graphic Books, former cinema The Projector, community library Casual Poet Library and National Gallery Singapore, each video features a local author, dressed in Chanel, seated beside a stack of books of their choosing. Through these titles, they reflected on childhood reading habits, and spoke about meeting literary mentors. They also ruminated on exploring emotional realms unlocked through fictional worlds.

That same warmth translates into the videos themselves. Through the lens, a love for reading and writing becomes almost tangible. Each frame is bathed in amber hues, reminiscent of spending an entire day lost in a book before arriving at golden hour. It is a sensory counterpart to the intimacy of being immersed in words.

An important angle to bring in, Chandreyee says, is the support and patronage of Chanel. “Within fashion publishing, no matter how interesting or novel the idea is, without financial backing, you can't realise it in a way that's equitable to the creatives who help bring a project like that to life,” she emphasises.

According to Chandreyee, fashion’s place in arts and culture is in its innate power to back thinkers, producers and disseminators of ideas that drive change for good. For this reason, she is a strong supporter of fashion brands using their resources to champion literary voices shaping arts and culture.

“Fashion brands dictate a lot of the zeitgeist. As much as they absorb and reproduce, they do a lot of agenda-setting on their own,” says Chandreyee, “My hope is that they continue to support writers who are mission-driven with a strong voice, and who ‘write for a living’. As that is becoming more precarious, it has also not been more important.”

Chandreyee spends time foraging bookstores in the city. She finds Singaporean author Jemimah Wei's debut novel at The Strand, one of NYC's most iconic bookstores.Image courtesy of Chandreyee Ray.

Recalling how she started out in fashion publishing, Chandreyee talked about interning at Harper’s BAZAAR Singapore when she was still in university. In 2020, she was recruited by then Vogue Singapore editor-in-chief Norman Tan to be part of the founding team. That was her first full-time job after graduation.

Joining a fashion magazine during early pandemic times is something Chandreyee describes to be transformative. Looking back, she says, “It made me feel a bit differently about that time—because of the dreaming and hoping that came with the idea of starting something new.”

Her experiences at the magazine allowed her to expand in ways that shaped her perceptions of cultural writing in Singapore. She elaborates, “My role started as a writer, where my job was really just to bring ideas to the table, and if those ideas were kind of screened and approved, I would be able to produce something out of it.”

Photo of past Vogue Singapore issues that Chandreyee posted on Instagram on the last day of her job. Image courtesy of Chandreyee Ray.

“Over the years, I realised that I was very much falling out of love with the fashion part. Not necessarily fashion itself… the fashion itself is still wonderful, you know?” Chandreyee pauses to reflect on her journey. We discuss the elephant in the room: It is difficult for many writers to remain enamoured with fashion magazine writing when so much of it revolves around selling the latest products. Still, she is grateful for her time at the magazine, as it brought her to the mentors who continue to shape her path.

She shares, “When it came to publishing, writing human interest stories is where I wanted to go.” She credits her former colleagues, who worked with her to build a cultural arm at Vogue. She says, “I could pick out the pillars and the stories that would make the section different and impactful from what already existed in the fashion and lifestyle publishing scene in Singapore.”

Over the course of five years, Chandreyee moved into the lifestyle section, grew alongside it, before leaving her role. Her time at the magazine saw her pen some poignant and thought-provoking pieces that captured her tenderness as a writer. Some of my favourites include an essay about the relationship with her immigrant mother and another one about the power of consent, which she penned after Chia Boon Teck, the former vice-president of the Singapore Law Society, questioned the judgement of sexual assault survivors.

Chandreyee’s shift into nonfiction writing was a natural next step for her. She explains, “I felt like being as persuasive as I could be in my writing was getting more and more important, because my positions and the issues I wanted to write about were becoming ‘less popular’ within mainstream fashion publishing.”

Butler Library at Columbia University, Chandreyee’s cocoon for reading & writing. Image courtesy of Chandreyee Ray.

The challenge in nonfiction is to do it beautifully, Chandreyee contemplates, saying, “It is finding ways to tell the truth over and over again, but in more and more interesting and compelling ways.” In New York, Chandreyee’s new season of writing begins. Her hopes are to improve her craft to relay truths that are urgent to tell. “Nonfiction is almost like service writing,” she adds.

Chandreyee names The Right to Sex, philosopher Amia Srinivasan’s collection of nonfiction feminist essays as one of her all-time favourite books. “I’ve read this book over three times now, and I think I only just got it,” she says with a laugh.

The Writing Life by Annie Dillard is another one of a selection of books Chandreyee brought with her to New York. The copy was a gift from a mutual friend Weiqi Yap, whom she first met at Vogue Singapore. “A lot of books like this try to teach you how to write. But this one is simply Dillard meandering through the pleasures and the pains of writing in all sorts of ways,” says Chandreyee. “It’s diaristic, beautiful, and reminiscent of the conversations that Weiqi and I have had. If there is one book keeping me connected to home, it is this. It reminds me of the kindred spirits I have met.”

Chandreyee at the Met Cloisters, New York. Image courtesy of Chandreyee Ray.

If she writes for a fashion magazine again, Chandreyee would love to converge her love for fashion and writing in what she calls sartorial writing: capturing the spirit of clothes as a way of exploring artistic and literary personas. A little like Charlie Porter’s What Artists Wear, she shares.

“I don't know if working in a fashion magazine or working in fashion publishing has shaped this,” she says, “but I love when literary writers use fashion as a vehicle.” She cites Joan Didion’s Blue Nights, in which garments become emblems of her grief for her daughter’s death.

“This, to me, is what I'm drawn to now,” she affirms. Whatever direction her writing takes next, it is clear Chandreyee is poised to shape it with both empathy and conviction. I feel lucky to be privy to this future writing, as much as I look forward to learning, reading and writing with her.

About the writer

Xingyun Shen is a fashion researcher, educator, and co-founder of the publishing project Clothes Press. Since 2020, she has been keeping a running list of literary quotations on clothing and dress drawn from her reading. She currently lives and works in Singapore.