Tin Tunsopon and the (Un-)Making of Thai School Uniforms

Unravelling structures of control in Thailand

‘ed·u·ca·tion·al’, post-thesis Autumn/Winter 2020. Image courtesy of post-thesis.

School uniforms in Thailand have remained almost unchanged for decades, functioning as a tool of governance that reinforces a standardised youth identity across the nation. Unlike most countries where uniforms are guided by local policy or custom, Thailand’s are enshrined in national law and heavily enforced by school personnel, with rules that extend beyond clothing to hair, nails, and makeup. Hence, when Bangkok-based designer Tin Tunsopon unveiled his graduation collection in 2019, the garments looked at once familiar yet shocking. Generations of students have donned the same collared, white shirts and navy or khaki bottoms that inspired the designer. But in Tunsopon’s hands, one of Thailand’s most regulated and recognisable forms of dress was unmade, taking on new silhouettes and exaggerated proportions that raises questions about what a uniform does and what a uniform could be—an inquiry he continues to explore through his label post-thesis. Tracing the history of student dress codes in Thailand reveals the complex entanglement of clothing, discipline, and power that Tunsopon’s work interrogates and unravels.

“Tracing the history of student dress codes in Thailand reveals the complex entanglement of clothing, discipline, and power that Tunsopon’s work interrogates and unravels.”

Tin Tunsopon’s creative reimagining of Thai school uniforms for his 2019 graduation collection. Image courtesy of Tin Tunsopon.

Thai school students in standard uniform. Photo by Peerapat Wimolrungkarat, from the Official Site of the Prime Minister of Thailand, public domain.

At its inception, Thai school uniforms were closely associated with loyalty to the monarchy and militaristic values.¹ They emerged in the early twentieth century as part of King Vajiravduh’s endeavours to secure Siam’s status as a siwilai (a localisation of the term “civilised”²) nation by positioning himself within a transnational ruling elite of civilised royalty. This necessitated fundamental changes in the way the monarchy was represented, but without a large royal family to serve as an extension of and amplify his siwilai persona, the king focused his modernisation reforms on his courtiers and servants instead.³ He encouraged the women to adopt Western aesthetics while, for the men, King Vajiravudh founded the Royal Pages College and the paramilitary group Wild Tiger Corp to recruit and groom his ideal subjects.

Drawn from all sectors of Siamese society, these young men lived under a strict code of conduct, pledged loyalty and fealty to the king in elaborate ceremonies and, most crucially, wore mandatory uniforms that symbolised their devotion.⁴ Enrobed and bounded by oath to the king(dom), they became living testaments to the transformative and performative powers of the uniform whereby one’s moral character could be moulded through and declared on the body.

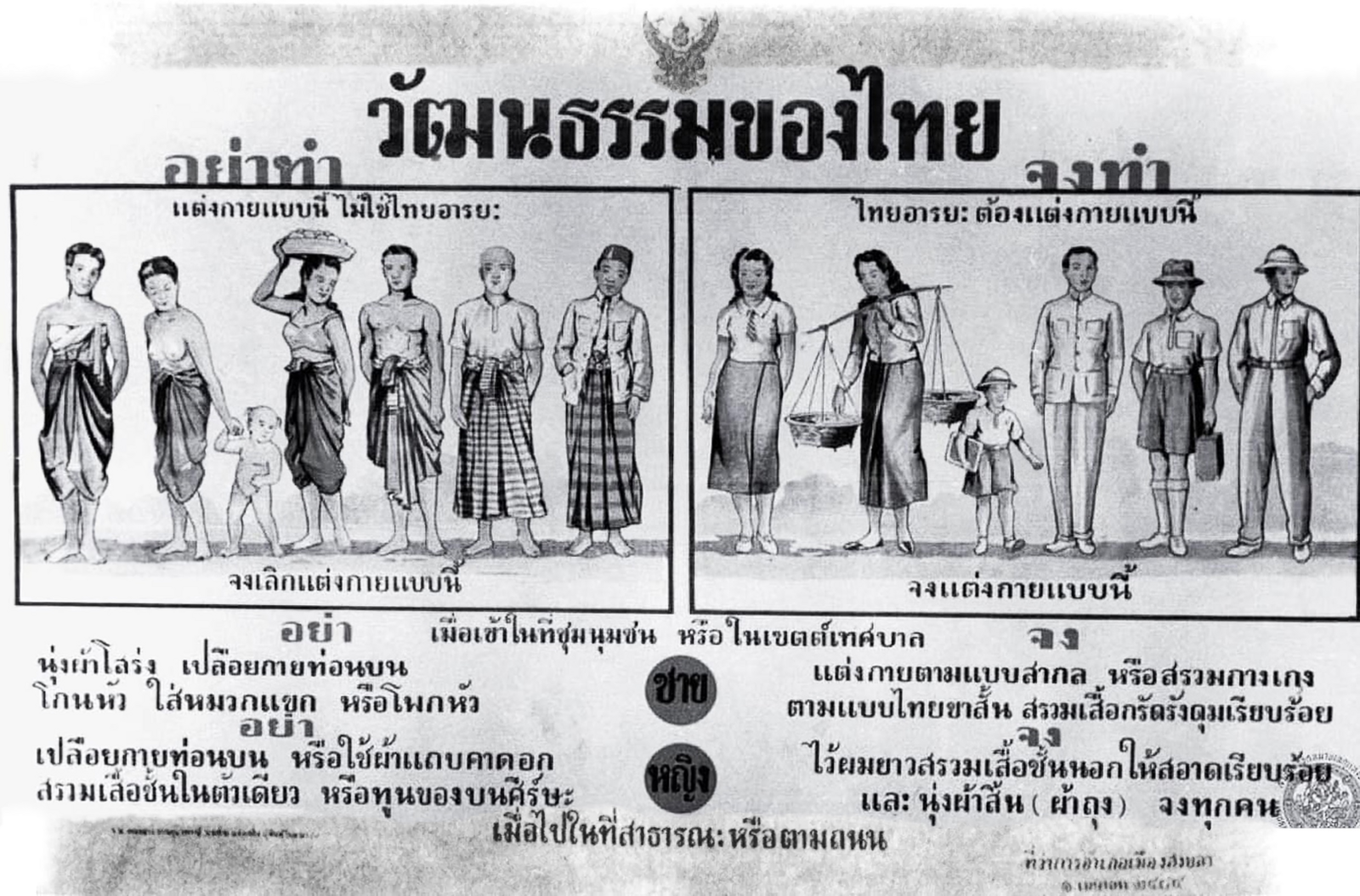

Poster illustrating Cultural Mandate 10, circulated by the Thai Government in 1941. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

It was under the authoritarian regime of Plaek Phibunsongkhram that student uniforms at both school and university levels were regulated nationally via the Student Uniform Act of 1939 and its accompanying Ministerial Regulations. The styles and colours of clothing, socks, and shoes, down to the size of hems and pockets, were standardised across institutions, reinforcing equality on the surface while crafting bodies that reflected the regime’s Cultural Mandates.

These are the twelve “state edicts” that Phibunsongkhram used to transform the Kingdom of Siam into the modern Thai nation following the abolition of Siamese absolute monarchy.⁵ One mandate, Cultural Mandate 10, bound notions of Thainess and its aesthetic to a state-specified, Western-aligned mode of dressing. A widely circulated poster contrasts two sets of figures: on the left, Thais are shown in what the regime deemed improper—traditional and local ways of self-presentation—while on the right, properly dressed citizens are neatly arrayed in Western-aligned outfits. A young student donning the newly standardised school uniform occupies this section, embodying what the subheading declares as a “civilised Thai citizen”.

Thai students with closely cropped hair for boys and ear-length bobs for girls, as mandated by the hairstyle regulation of 1972. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

While denying its royal roots, Phibunsongkhram built on King Vajiravudh’s logic that the sartorial realm could be mobilised as a tool for disciplining citizens in the name of national progress. The new dress code was presented as civilised, moral, and a patriotic duty. This logic resurfaced under military dictator Thanom Kittikachorn, who extended the regulation on students’ appearance beyond clothing as a blunt instrument to suppress identity and autonomy at a time when campuses were hotbeds of activism. Student protests in Thailand had begun tentatively in 1968, fuelled by decades of authoritarian rule, socio-economic frustrations, and inspiration from anti-war and leftish movements around the world. By 1972, they had become more organised and confrontational.⁶

In response, the regime issued a new regulation mandating cropped hair for boys and ear-length hair for girls, while banning cosmetics, jewellery, and dyed hair as “inappropriate to the status of students”. Teachers, in turn, wielded scissors as a tool of enforcement, cutting students’ overgrown hair in front of their peers or during large assemblies to publicly shame those who refused to comply.⁷ These rules defined the bodies of students for decades, until they were formally replaced by the Student Uniform Act of 2008. Issued under the interim government of Surayud Chulanont, who stepped into power in the wake of the 2006 coup d’état, the new law was billed as a necessary revision to an outdated legislation.

‘Rule Breakers’, Wacoal X post-thesis. Image courtesy of post-thesis.

For students who had grown up under the 2008 Act, however, uniforms no longer signified civility or equality but a lingering apparatus of authoritarian control. The very precision with which the state continued to legislate hems, hair, and nails, made clear that student uniforms were a tool for disciplining young bodies rather than simply clothing them.

Tunsopon was among the first to articulate this issue, his graduation collection anticipating the debates that would surface a year later, in 2020, when tens of thousands of young Thais took to the streets to demand for democratic reforms. Secondary school students mobilised in unprecedented numbers, challenging not only the government but also the culture of control embedded in the classroom; they were frustrated that school authorities prioritised arbitrary grooming regulations over teaching quality.⁸

Campaigns like “เล็บกู ผมกู ร่ายกายกู แต่ไปหนักหัวครู 1 ธันวาบอกลาเครื่องแบบ” (“My nails, my hair, my body, but somehow my choices bother the teachers, so say goodbye to uniforms on December 1”) encouraged students across Thailand to abandon dress codes and symbolically ‘return’ their uniforms to the Ministry of Education on the first day of the semester. Other demonstrations highlighted the humiliation of gendered restrictions and forced haircuts through creative performance pieces.⁹

‘senpai(olo)gy’, post-thesis Spring/Summer 2023. Image courtesy of post-thesis.

In solidarity with the movement, Tunsopon, as the founder and creative director of post-thesis, joined forces with the lingerie brand Wacoal to launch the ‘Rule Breakers’ collection—its title perhaps a subtle nod to the ‘Bad Student’ activist group that spearheaded school-based protests across Thailand. The collection comprised four designs, each developed to conform to student dress codes but carrying within them the potential for transformation. Hemlines are adjustable and alternative components, such as add-on sleeves, can be layered to redefine the standard silhouette of the uniform. If his graduation collection boldly unmade and remade the uniform, this project worked more covertly to unravel the garment, drawing on the quiet tactics Thai students have long used to resist the strict codes—rolling sleeves or shortening hems.

‘Ceremony of Innocence’, an unreleased project that examines bridal wear as a type of uniform. Image courtesy of Tin Tunsopon.

Today, post-thesis continues the inquiry that fuelled Tunsopon’s thesis collection by introducing bold new colours, silhouettes, materials, and interesting references to Thai school uniforms with each new collection. The designer’s understanding of the term has also expanded, most notably in his ‘Ceremony of Innocence’ garment (an unreleased project), which examined bridal wear as another kind of uniform—one that similarly encodes ideals of purity and obedience. But it is against this history of regulation and control that Tunsopon’s work becomes so provocative and so resonant with a younger generation, the ‘Rule Breaker’ collection drawing significant media attention and quickly selling out. In the hands of Tunsopon, the uniform is never fixed but constantly open to redefinition. While his graduation collection made visible the invisible threads of control—seen only in their unravelling—his ongoing work with post-thesis continues to pull at these threads by redefining the relationship between uniforms, power, and the body.

Notes

Moodjalin Sudcharoen, “Migrant Youth Identities as Performances: Dress Codes and Styling in Thai Multi-ethnic Education”, Asian Ethnicity 24:4 (2023): 601.

Thongchai Winichakul, “The Quest for ‘Siwilai’: A Geographical Discourse of Civilizational Thinking in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Siam’, The Journal of Asian Studies 59:3 (2000): 529-531.

Kanjana Thepboriruk, “Dressing Thai: Fashion, Nation, and the Construction of Thainess, 19th Century–Present”, Journal of Applied History 2 (2020): 115; David Malitz, “The Monarchs' New Clothes: Transnational Flows and the Fashioning of the Modern Japanese and Siamese Monarchies”, in Transnational Histories of the ‘Royal Nation’, eds. M. Banerjee, et al. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 157.

Thepboriruk, “Dressing Thai”, 115-116.

Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, A History of Thailand, fourth edition (Cambridge University Press, 2022), 146-147, 149.

Baker and Phongpaichit, A History of Thailand, 208.

Maroosha Muzaffar, “Thai school apologises after student's ‘punishment haircut’ sparks outcry”, Independent, 21 July 2025, https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/southeast-asia/thailand-school-punishment-haircut-outrage-b2791563.html.

Kanokrat Lertchoosakul, “The White Ribbon Movement: High School Students in the 2020 Thai Youth Protests”, Critical Asian Studies 53:2 (2021): 210.

“Thai pupils fight for the right to be hirsute”, The Economist, 6 August 2020,https://www.economist.com/asia/2020/08/06/thai-pupils-fight-for-the-right-to-be-hirsute.

Sources

Baker, Chris and Pasuk Phongpaichit. A History of Thailand, fourth edition. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Koh, Ewe and Thanyarat Doksone. “Students now free to choose their hairstyles, Thai court rules”. BBC News, 7 March 2025, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cj67yj1kj36o.

Lertchoosakul, Kanokrat. “The White Ribbon Movement: High School Students in the 2020 Thai Youth Protests”. Critical Asian Studies 53:2 (2021): 206-218.

Malitz, David. “The Monarchs’ New Clothes: Transnational Flows and the Fashioning of the Modern Japanese and Siamese Monarchies”. In Transnational Histories of the ‘Royal Nation’, edited by Milinda Banerjee, et al. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Muzaffar, Maroosha. “Thai school apologises after student's ‘punishment haircut’ sparks outcry”. Independent, 21 July 2025, https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/southeast-asia/thailand-school-punishment-haircut-outrage-b2791563.html.

Sudcharoen, Moodjalin. “Migrant Youth Identities as Performances: Dress Codes and Styling in Thai Multi-ethnic Education”. Asian Ethnicity 24:4 (2023): 588-609.

“Thai pupils fight for the right to be hirsute”. The Economist, 6 August 2020, https://www.economist.com/asia/2020/08/06/thai-pupils-fight-for-the-right-to-be-hirsute.

Thepboriruk, Kanjana. “Dressing Thai: Fashion, Nation, and the Construction of Thainess, 19th Century–Present”. Journal of Applied History 2 (2020): 112-128.

Winichakul, Thongchai. “The Quest for ‘Siwilai’: A Geographical Discourse of Civilizational Thinking in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Siam”. The Journal of Asian Studies 59:3 (2000): 528-549.

About the writer

Weerada Muangsook is an art and fashion historian whose research lies at the intersection between dress, identity, representation, and power. She is currently a PhD candidate in Art History at the University of St Andrews.